“Preventing the occurrence of thoughts” really means seeing What Is beneath and prior to it all. For when there is, as Zen says, no-thought or no-mind, then there is realization. On the other hand, there is room in self-inquiry for some “delicate muscle” to be applied: really wanting to know Who I Am, I, as personal consciousness, may need to experience fewer and fewer thoughts first. On the one hand, self-inquiry has nothing to do with the suppression of thought (cf. Preventing the Occurrence of Thoughts.– This pointer requires some finesse.“Who am I?” means, really, “Who is that which is really asking the question, who is that from which this question arises, and who is that to which this question returns? Who, in brief, is aware of all of this?” In Zen speak, there can be, as the inquiry deepens, a greater and greater sense of “I don’t know.” The finite mind starts to realize that it cannot know its Source.

Once, via early meditations, such powers have been strengthened, then Ramana’s counsel is to the point: concentrate on finding the source of the person/personal consciousness/ego-self. That preliminary step involves strengthening considerably the powers of concentration first.

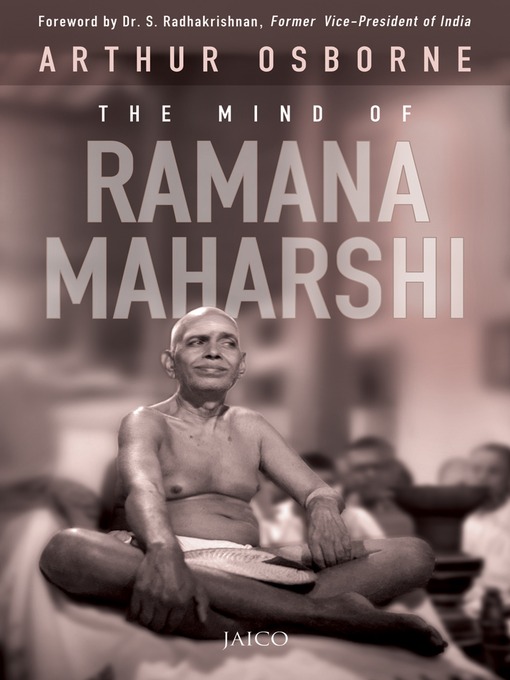

As a genuine line of questioning, the question, well, needs to be deeply registered as a question. While a mantra is repeated time and again and while a mantra is a sacred sound, self-inquiry is indeed a mode of questioning. The Difference between a Mantra and Self-inquiry.– As Chan master Sheng Yen also states, self-inquiry (akin to huatou) is not a mantra.Ramana’s very succinct instructions can use some unpacking. In the “Preface” to The Collected Works of Ramana Maharshi, Arthur Osborne includes an elegant summary of self-inquiry in Ramana’s words: “It is not right to make an incantation of ‘Who am I?’ Put the question only once and then concentrate on finding the source of the ego and preventing the occurrence of thoughts” (p.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)